During 2020, and even more so in 2021, electric cars began to eat into the popularity of cars with combustion engines, both in terms of media and political interest, and in terms of sales. There are more models in showrooms and more test drives than ever before.

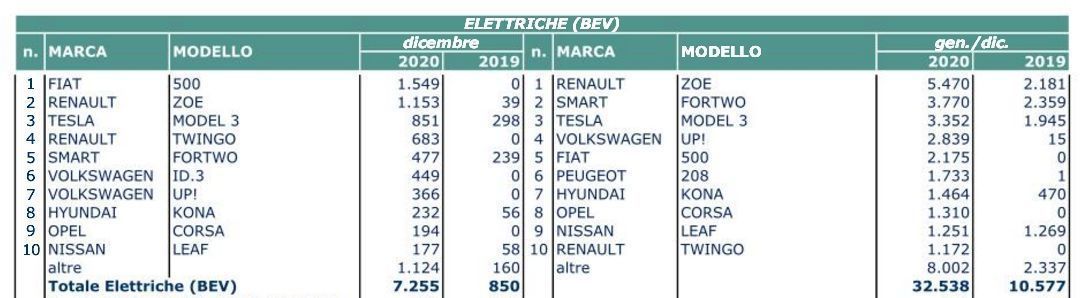

What is 2020’s legacy, in terms of the car market? The overall trends are clear: electric cars are an increasingly popular and tangible phenomenon in many parts of the world, Italy included. People looking to the long-term and people who are ecologically minded or passionate about the electric mobility revolution will be happy at receiving any news of this kind. Today, the market has seen triple-digit percentage growth in sales of plug-in cars, the highest growth figures ever, and, in Italy, BEV models have broken the 5% barrier in terms of sales volume. This seems like a small figure but, when compared with sharply falling general sales and in light of industrial and political trends, it’s actually an excellent jumping off point.

PHEVs recorded annual growth of +319%, whilst BEVs were +207%. Both categories of electric car are the fastest users of charging points and it’s no coincidence that in Italy in the last year, the number of charging points has doubled. For the first time, looking ahead to 2021, there are electric cars in all market segments, right up to the high-performance GT sector, with the latest release of Audi’s e-tron GT RS. This is a car that Audi itself says is its best and highest performing model ever. To give the concept credibility, it’s being manufactured in their Sport division, alongside the legendary R8 (a cousin of the Lamborghini).

From the small Renault 5 BEV promised by its CEO, Luca De Meo, suited to all budgets, to the first electric Ferrari announced< by its president, John Elkann, this is a 360º strategy which will appeal to every taste in terms of style, size and performance. In a few years’ time, with the introduction of Euro 7 standards, almost all new cars will be plug-in, effectively putting an end to combustion engines, and public charging points will be essential, especially for intensive use or for long journeys. It seems absurd but it’s not just city cars that can be fully charged for just a few Euros, supercars worth hundreds of thousands of Euros can be “filled up” at the charging point for the same amount of money that once upon a time wouldn’t have put enough petrol in to fill the reserve. However, the real hot topic lies outside the automotive sector. The big question is about regulation through incentives, what are countries doing in this regard?

Are Italy’s politicians doing enough on this? Our often choppy political waters don’t help. Whatever information enthusiasts have learnt over the past few years, isn’t always in the public domain, at least not in Italy. Besides the work done on publicising the large incentives, this is something which Government and other public bodies can do better. A recent opinion poll (1000 people interviewed by Citynews and 2BResearch) shows that Italians still don’t know a lot about the transition to electric cars. If it’s true that young people are generally interested in electric cars, even before they get their licence, it’s also true that more than half of those interviewed have no clear idea of the differences between BEV, HEV, MHEV and PHEV cars.

In particular there’s a North/South divide in Italy, in terms of knowledge on the subject and the prevalence of the required charging points. This is a real focus point. The biggest issues in the minds of anyone thinking of buying an electric car for the first time are the initial cost, which can be cushioned by heavy incentives (which in some Italian regions involve five-figure sums, for scrappage schemes) and fears about charging. Here, it should be reiterated that it’s not just car manufacturers and the automotive industry that should be involved in the widespread installation of charging columns, it should also include public bodies in partnership with independent stakeholders, such as Be Charge. Today, when you think about the range of a small electric car (from a Zoe to a Fiat 500), real enthusiasts think that 250-300Km is a valid real-world figure, which is lower than the declared WLTP figures, and generously estimating average consumption in Italy, as read or seen in many test-drives, as being between 13 and 20 kWh/100 Km. But what about charging systems and real-world charging times? This is where experience and knowledge need to be shared. It would be good if some European funds were to bridge the gaps in knowledge, allowing people to find out for themselves, and from independent sources, whether

In Collaboration with: